The Team

Their Story: The Challenge

An old East Indian legend tells of six blind men exploring an elephant by touch, with the goal of discovering what the elephant looked like. Because each man touched a different, very specific part of the elephant, they failed to see the “big picture” of the whole elephant. This was captured perfectly in the verse of John Godfrey Saxe's poem “The Blind Men And The Elephant”: “Each in his own opinion, Exceeding stiff and strong/Though each was partly in the right, [A]ll were in the wrong!”

Current education paradigms are very much like those blind men. Most schools and universities encourage students to “feel the elephant” in only one very specified subject field, while discouraging or even preventing them from learning about other subjects in depth, though the desire and ambition are there on the students' part. This leaves metaphorically blind graduates who are often unable to move out of the narrow, arbitrarily defined box of their field, and thus they often fail at attempting to solve problems in their field that require more subject integration or a broader knowledge base.

The Project Polymath Trustees have all experienced the frustration of narrow, hyper-specialized educations when they sought a wider base of knowledge and experience in their academic careers. While their stories are varied, common themes thread through all: frustration with a status quo that seeks to narrowly define students' life ambitions, discouragement, perseverance, and the desire for setting a new paradigm that better paves the way toward educational triumph and a better society.

Michael's Story: Blind Universities

Since childhood, Dr. Michael Barnathan (Project Polymath founder) wanted to create an intelligent machine that would cure cancer. He taught himself computer programming at the age of 7, but he spent the next 20 years discouraged, dissuaded, and punished by his teachers for following his dream. In the classroom, teachers considered him “difficult” because he asked too many questions, had too much energy, felt too deeply, and spent too much time on the computer. They decided he had Attention Deficit Disorder and referred him to doctors, who denied the teachers' “diagnosis.” Frustration after frustration followed.

Michael persevered - in spite of his teachers - and continued to develop his gifts and abilities, achieving mastery in computer programming and a wide swath of technical disciplines after over a decade of opposition and defiance. Although Michael's high school grades were poor because he prioritized development over his high school classwork, Michael graduated valedictorian of his college, because he prioritized development over his high school classwork. Unifying his high school, undergraduate, and graduate experiences, Michael continued to pursue his dreams, specializing in artificial intelligence and bioinformatics. Yet when it came time to add a formal medical education in order to complete this arsenal, Michael was actively denied the ability to attend courses in medicine, on the grounds that they were “outside of his major.” Seeing another 10 year battle looming on the horizon, Michael then realized that something was deeply wrong with an educational model that attempted to cram students' life dreams and goals into predetermined, neat, stifling little boxes. Education should support the full creative potential of every individual student, or else it has failed in its quest. It was under the banner of this mission that Michael founded Project Polymath, gaining a new passion in education which led to a year of adjunct teaching at the university and graduate levels, and going university-to-university helping high school teachers improve their STEM retention rates.

Though Michael retains his passion in education to this day, the upper echelons of academia focused too much on tiny, incremental research questions, and Michael realized that he would never be able to pursue his goals under that framework. Following his successful doctoral defense, Michael left academia and, with no formal medical training or network, began the painstaking process of building up a medical education from scratch. Lacking a team, lacking resources, and lacking social endorsement for his pursuit, Michael founded a diagnostic company called Living Discoveries to pursue his medical aspirations. He took a job as a Senior Software Engineer at Google to fund this passion in its early stages.

Despite all the obstacles, the technical progress of Living Discoveries was unstoppable. Blending his strong computational background with a voracious hunger for medical knowledge, Michael created a computer program in 2011 which, for the first time, could diagnose breast cancer in a screening mammogram with greater accuracy than a human. But even then, Michael could not find an endorsement. He had completed the prototype and worked tirelessly to get it on the medical market, but it sat there. Calls to doctors and investors? Unanswered. Emails? Disappeared. No one would even consider it without a doctor involved. For nearly a full year, a groundbreaking, lifesaving piece of technology went completely unused, because the school system did not allow Michael the formal medical training that would get companies to take a second look.

Michael eventually found a medical co-founder and, having set the job at Google aside to pursue his vision, is forging ahead relentlessly with both Project Polymath and Living Discoveries.

The vision of Project Polymath isn't necessarily to solve the “blindness” of the Indian men in the legend. It is to remove the existing and perceived walls which prevent each of our students from exploring the world's elephants from trunk to tail, so we collectively have a larger, more complete picture of existing problems and their solutions.

Jenelle's Story: Blind Teachers

Jenelle learned to read at age two, and she often devours several books simultaneously. In elementary school, she enjoyed playing chess, learning algebra, and doing class projects in her school's gifted program. In middle school, however, things changed. School became a place of war and survival; Jenelle's classmates kicked her, threw objects at her, sent her nasty notes during class, and threatened to beat her up and kill her. The teachers were aware of the situation but did nothing; they accepted her peers' behavior as normal. So Jenelle refused to go to school. She missed six weeks straight of class, pretending she was sick. She still did her schoolwork from home and graduated eighth grade at the top of her class, but the damage was done. Because of the negative academic environment and lack of support, Jenelle learned to view school as a necessary evil rather than a vehicle to future success.

Jenelle was high school valedictorian out of almost 700 students, National Merit Finalist, and the winner of multiple academic medals. Yet, because of what she learned from her teachers and peers, she went to Northwestern University with her passion for academics almost completely snuffed out. She had no idea what major to choose, because she was talented at most subjects but no longer enjoyed any of them. She took a six-month break and transferred schools; at her new university she finally met like-minded peers who encouraged her intellectual interests, and she was able to start truly enjoying academic pursuits again. When Jenelle finally found an environment which supported her growth, she was able to discover and pursue her passions.

Jenelle now holds a Masters in Mental Health Counseling and works with teens and their parents. In the past two years, she has also led therapy groups in a psychiatric hospital, written marketing and business plans, developed a parenting curriculum for her church, co-led nursery school classes, volunteered at cat rescue shelters, and designed neuroscience presentations.

Project Polymath works at addressing students as whole individuals. We do not focus solely on students' academic performance; we aim to also help our students with character and moral development, emotional health, personal growth, and social development.

Kristi's Story: Blind Society

Kristi was an avid learner from an early age. She loved coordinating science experiments with other neighborhood children and when left unsupervised, she would disassemble anything she could find. Kristi often got in trouble for questioning rules and was frequently punished for refusing to follow the ones she thought illogical or unhelpful. At school, she learned to sit quietly and jump through hoops, though her independent spirit still showed. Kristi refused to do rote homework that seemed of little practical benefit, and she daydreamed about going to college and commanding her own academic destiny. Educators saw Kristi as a “teacher's pet” and often paired her with underperforming students in effort to keep Kristi busy while simultaneously giving them extra help. Looking back, Kristi often and openly wonders what would have been different if her teachers would have challenged her with additional, more advanced work instead of attempting to “keep her with the pack.”

Kristi shined in high school. She was a leader in student government, started a city-wide youth volunteer organization that was mentioned several times in the newspaper, consistently made honor roll in the gifted education program, and lined her schools trophy cases with debate and oratory competition awards.

Despite this, the system tried to thwart Kristi’s success at every turn. After Kristi was granted a rare opportunity to do an interview for local TV about her volunteer charity for city-wide youth, Kristi’s principal was to provide transportation to the site. When she arrived at his office on time and ready to go, he told her that he had cancelled the event because he had to deal with disciplining other students. This was the first of many times when Kristi’s achievement and positive movement were thwarted for the benefit of those who had no inkling or desire for students’ scholastic success. Faculty were equally culpable: Kristi asked repeatedly to be moved from her sophomore American Civics class because the teacher made a habit of handing out videos and worksheets, then disengaging from the classroom, balancing his personal checkbook by the glare of AV equipment. She eventually won this battle, though it took an entire semester.

In her Junior year, Kristi had the opportunity to enroll in a program which would have allowed her to complete early college credits, but her guidance counselor told her that the school would not allow her to partake in it because she lacked a typing class credit. Kristi was already a proficient typist, and proposed that she would happily take any typing test if she could skip that class on her transcripts, but the guidance counselor adamantly refused to let her do so. That was the straw which broke the camel’s back. For a semester, Kristi warmed a seat until she became of age to withdraw, then , packed her books and firmly quit high school. She refused to participate in a system which focused on by-the-book requirements at the expense of hindering her growth. She then enrolled, with no GED or diploma, in the Honors Philosophy program at a local community college. This event marked the beginning of Kristi's true education, turning her back on the gesturing of the status quo and utilizing her mind, her ability, and her achievements to pave a better way.

Kristi now holds a BA in Network Management and runs her own business that continues to grow despite the difficult economy. She has also written a homeschooling curriculum and started a homeless ministry which served 2,000 meals in less than a year.

Project Polymath provides flexible student coursework and schedule requirements. Within the framework of university accreditation criteria, our focus is on supporting each individual student's aptitudes, interests, and goals.

The Solution:

An Interdisciplinary…

We envision Polymath University, a university where students are taught to creatively fuse several areas of study from the very start of their training. For someone like Michael, we would provide an individualized combination of computational studies and classes in medicine, so he would have the tools to achieve his goals of creating an AI device to diagnose and cure cancer. He would also be taught to intuitively connect methods from both fields in our integration seminars, yielding a great deal of insight in bioinformatics and related disciplines. Also, because such an approach cross-cuts yet exposes students to the same level of depth as a set of subject-specific courses, Michael would graduate in four years with the equivalent of multiple college degrees and a large body of demonstrated real-world experience.

Modular…

We wish to avoid holding students to canned career or life expectations, preferring to give them the tools required for them to pursue their life goals. We eliminate redundancies in training, allowing students to fulfill all credit requirements by demonstrating proficiency through their choice of examination-based waiver, coursework, independent projects or theses, independent or group research, or industrial activities (i.e., internships). In all cases, comparable skillsets and proficiency must be demonstrated by students and approved by faculty for students to advance. Students' curricula would be highly customizable and problem or goal-oriented rather than subject-oriented. For a student like Kristi, we would easily waive a typing class requirement, allowing her to test out of it by demonstrating proficiency.

Coursework would be evaluated through a Montessori-style system of “topic units”, in which students can elect to “graduate” one course and enroll in another at any time during a semester, so Kristi would be able to take elective college credits at her own pace. If Kristi desired to do research, she could work in a “research group” composed of fellow students, faculty, or a mix both. Kristi could freely pursue her own individual interests, rather than being bound to professors' interests in the infamous “publish or perish” cycle. Also, if she wanted to start a business based on her work, our incubator would guide and train her throughout the process.

Our standards are high, but we give students a considerable amount of support to meet and surpass them. Within-subject proficiency is expected at the same level as any other university (though we suspect that many students will exceed it and receive multiple certifications), and is measured through projects, courses, exams, and other tangible demonstrations of ability. Students are also expected to demonstrate an ability to think creatively and draw upon multiple fields of study.

Self-Determined…

We focus on students' personal growth and development, and we desire for our students to meet similar ideals such as those in Maslow's concept of self-actualization or Dabrowski's positive disintegration - theories which have found their greatest practical application in modeling the development of the world's most gifted students. For a student like Jenelle who is undecided about what subject field to pursue, we would assist her in discovering her academic passions and choosing a field of study, and we would help her develop the insight, confidence, and experience required to pursue the challenges that society will set before her. During the first year, we offer a “Great Ideas” elective which surveys a basic topic in a different field of study every day. This allows students to rapidly discover their passions.

Since our classes focus on subject integration, Jenelle would easily be able to take on new subjects and react to changing interests without losing time. She would also likely discover her strongest interests more quickly and easily, because our program has students exercise a great deal of personal choice, which in turn ensures that their values are more fully developed and their ultimate visions are well-defined and in line with their training.

By the time a student like Jenelle graduates from Polymath, she would not only be well-versed, but further along in her human development and realization of her full potential.

Creative…

Students would be creators, adding to their societies even before graduating. The difficulties Michael encountered would be removed, because creative pursuits that solve real problems are part of the culture. Also, the very environment of the university would inspire the act of creation. Michael would walk the halls of a university where student-created art adorns vibrantly-lit halls, student-created ambient music fills comfortable and well-furnished common areas, and spacious areas of untrammeled natural beauty exist for students to explore around campus.

Michael would find ample facilities for studying, as well as many opportunities to refine his own thoughts on nature walks or other activities. Our enriching environment would include planned facilities such as a comfortable and extensive library (with amenities resembling most large bookstores, such as couches and a coffee shop) and “The Polymath Museum of Art and Science”. We believe that such an environment would provide an incomparable source of ideas and motivation for our students.

It should be emphasized that, like Einstein, we would greatly prefer students to think and create for themselves over simply regurgitating the thoughts of others. Students like Michael would be “incubated” while they engage in the uniquely human activity of creation which ultimately benefits the world at large.

Lifelong…

Unlike many universities, our students' educations would not stop at graduation. Students like Jenelle who have changing and varied interests would be able to nurture their curiosity for a lifetime. Learning never stops, and there is no reason to deny an education to those who could benefit from it. Therefore, Jenelle would be entitled and encouraged to sit in on as many courses given at the university as she wishes, for free and for the rest of her life (classroom space permitting). We believe this policy alone will significantly improve interest in learning and overall quality of life, especially if it is also adopted by other institutions in response. It is a three-fold benefit: students like Jenelle have the perpetual opportunity to pursue continued education, first-time students in class with her have the opportunity to learn from Jenelle’s experience, and the new opportunities opened up by the class indirectly increase the university's prestige through Jenelle's future work.

University.

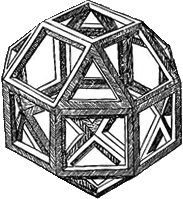

Polymath would be a new type of university - the first to live up to its name and grant a fully universal education to its students. We ultimately hope that by graduating an unprecedented number of interdisciplinary leaders like Kristi, Michael, Jenelle, and countless others, we will usher in a wave of artistic and scientific advances culminating in a second Renaissance.